Does Male Competition Help Explain Human Sex Differences in Body Size?

Anthropologist Holly Dunsworth has a new paper questioning the common emphasis placed on sexual selection for explaining sex differences in human height. She noted on Twitter that the research for her paper was kick-started by a disagreement she had with evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne on the same topic a few years ago. Jerry Coyne’s post on the matter can be found here.

To start with, I will say that, despite disagreeing with her broader argument, I think there are two important contributions Dunsworth makes in her paper.

First, Dunsworth emphasizes the importance of considering developmental factors for understanding the emergence of physical sex differences, and discuses the role steroid hormones like estrogen play in long bone growth. I found this section interesting and think exploring how developmental factors contribute to physical sex differences is a valuable line of research.

Second, Dunsworth appropriately notes that certain sex differences in body size is an ancestral condition shared with nonhuman apes. Dunsworth writes,

Great apes develop sex differences in body mass like humans do, where both sexes follow similar growth trajectories until the pubertal transition when the females stop growing and the males continue to grow for a longer period of time. Though levels of sex differences in body size differ between species, among the living hominids (great apes and humans) there is likely to be significant shared fundamental biology of reproduction and skeletal growth. Thus, the existence of human sex differences in stature is rooted in ancestry.

I think this is a valuable point, and in fact, as I will explain, I think this idea actually helps explain why both Coyne and Dunsworth come to, in my view, somewhat misleading and/or premature conclusions.

Now, if Dunsworth were to focus entirely on the role of sexual selection for explaining sex differences in human height alone, I think the reference to ancestral patterns would raise some useful questions about the necessity of a sexual selection explanation, as it could instead represent a largely conserved ancestral pattern that did not necessarily require sexual selection on human males or more recent human ancestors per se (more on this later). However, Dunsworth wishes to extend her critique across other primate species, writing that,

Yet even within this more complete “ultimate” narrative, with selection optimizing the two sexes' skeletal growth separately, the sexual selection perspective on male height seems unnecessary. That provocative last sentence is not a claim that the sexual selection explanation is wrong or that it is implausible. But in light of what is known and still unknown about skeletal development and its relationship to the endocrinology of reproduction, suddenly there is room for skepticism about the relevance of male competition and female choice as an explanation for the existence of sex differences in stature, let alone its singular dominance of the narrative. More work is needed if sexual selection is to be held up as the explanation for why male hominids [great apes] have longer bones than female hominids do.

I think it is important not to conflate ‘male competition’ and ‘female choice’ as explanations—even if there may be overlap in some cases, they can be quite distinct. I will focus here on male competition specifically (Dunsworth also usually refers to the male competition explanation in the paper, despite occasionally mentioning female choice). Dunsworth writes that,

the traditional and enduring textbook explanation for sex differences in hominid body size is sexual selection—with large ancestral males winning competitions, which boosted their reproductive success compared to smaller males. Because gorillas have both intense male competition and large male bodies, the mere existence of sex differences in human body size serves as evidence of sexual selection being the driver of these differences. But as Plavcan has cautioned, there is not a straight-forward relationship between sexual selection and primate male body size, largely because the sorts of data that are required to investigate this relationship are difficult to obtain.

Unfortunately, I think this reference to Plavcan’s work ends up being quite misleading. The two papers that Dunsworth cites here are Plavcan (2001) and Plavcan (2012). I think both papers severely undercut her argument rather than bolstering it.

In his conclusion, Plavcan (2001) writes,

It is now apparent that sexual selection, mating systems, and estimates of the frequency and intensity of male-male competition do not measure the same thing. This leads us to the conclusion that sexual dimorphism is not a simple function of differential male reproductive success, but also of pressures on males for display, of the interaction between the utility of different traits as weapons and different fighting strategies at different sizes and in different habitats, and of female counterstrategies against male domination of mating patterns. Dimorphism is also a function of different developmental pathways, all of which can be affected by different selective pressures throughout an animal’s entire life-history. Understanding these pathways and the selective forces that mold them gives profound insights into the evolution of dimorphism.

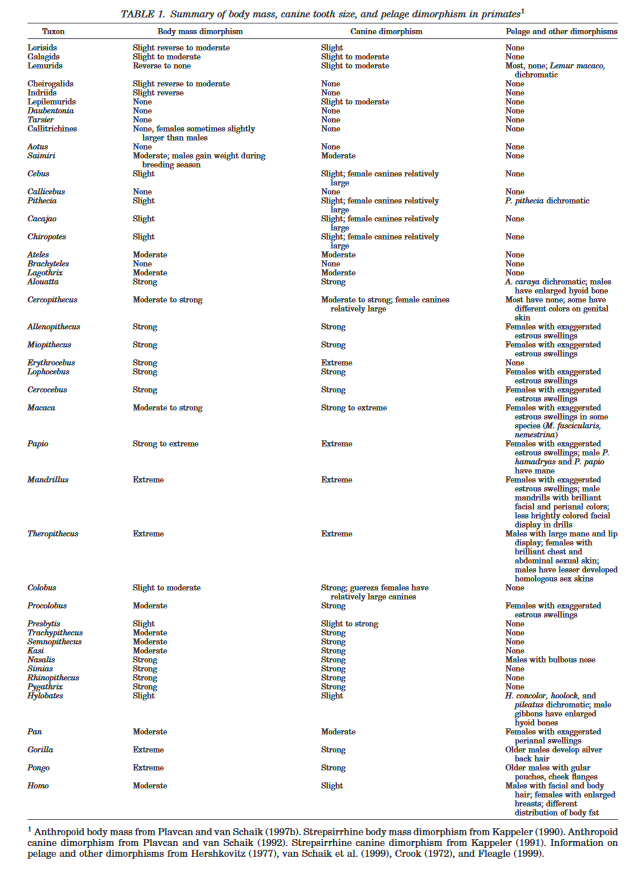

Notably while Plavcan, like Dunsworth, gives appropriate credit to the role of developmental pathways and multiple contributing selection pressures for understanding patterns of sexual dimorphism across primates, he, unlike Dunsworth, very strongly emphasizes the role of (multiple forms of) male competition in contributing to these patterns, for reasons that are apparent in the data he provides. For example, consider this table:

From Plavcan (2001).

As can be seen here, and as he discusses in the paper, there is a clear relationship between body mass dimorphism and canine dimorphism. This pattern seems very difficult to explain without male competition playing a significant role in explaining size dimorphism across primates, considering the importance of canines as weapons and intrasexual signaling in conflict across primates.

Notably, humans also still have some sexual dimorphism in canine height, comparatively small though it is.

From ‘The Evolution of the Human Mating System’ by Muller & Pilbeam, in Chimpanzees and Human Evolution (2017) edited by Muller, Wrangham & Pilbeam.

Since in humans canines no longer function as useful weapons or for signaling purposes, this may actually bolster the case that some aspects of human size dimorphism represent a conserved ancestral pattern (perhaps a developmental suite of features) that need not necessarily be due to sexual selection in humans or more recent human ancestors specifically (contra Coyne’s direct focus on this point). However, it conflicts with Dunsworth’s de-emphasis on male competition across hominids more broadly.

Plavcan (2012) is even more explicit in emphasizing male competition and disagreeing with the account offered by Dunsworth. He says it very clearly,

There is no species of primate that shows strong size dimorphism without male competition and polygyny. Two cercopithecoid taxa were thought to show a combination of strong size dimorphism and monogamy (Cercopithecus neglectus and Simias concolor; Leutennegger and Lubach 1987). Further study of both of these species demonstrated that polygyny is present in other parts of the species range and that hunting pressure explained the presence of monogamous pairs at least in S. concolor (Brennan 1985; Watanabe 1981).On the other hand, there are no monogamous or polyandrous anthropoids that show strong size dimorphism, though several monogamous species do show modest levels of size dimorphism (Plavcan 2000a, 2001). If selection to alter female size—either larger or smaller—is common independent of changes in male size and contributes significantly to inter-specific variation in size dimorphism, then we should expect to see greater variation in dimorphism among monogamous and polyandrous species. That this is not the case suggests that large male size in dimorphic species is maintained in spite of pressure to reduce male size to that of females and that most substantial dimorphism in primates is a function of changes in male and not female size [emphasis added].

In a more recent article, Plavcan (2018) even notes that while, “Modern humans are characterized by a modest degree of size dimorphism—about 15 percent on average across populations,” and that “This magnitude of dimorphism falls within that seen in modern gibbons and is less than that of chimpanzees,” he also mentions that, “modern human males are substantially more muscular than females, and “lean-mass” dimorphism is comparable to the size dimorphism of chimpanzees,” perhaps pointing to how focusing on simple metrics of size may obscure other important sex differences relevant to male competition.

Now, while I do think it is quite uncertain what role sexual selection in humans and recent human ancestors specifically may have played in influencing patterns of sexual dimorphism, there is a great deal of research indicating a significant relationship among human males between status and height/body size, consistent with broader patterns in primates as well. ‘Big man’ is an extremely common designation for a leader across small-scale societies and even some nation states. For example, the Sumerian term for ‘king’, Lugal, is GAL+LU = BIG plus MAN. Across nonindustrial societies larger and higher status men tend to have greater reproductive success, although importantly this relationship seems to be substantially smaller (r = 0.19) than that found across nonhuman primates (r = 0.80).

“Comparing weighted effect sizes of men’s status on measures of RS, from the model with subsistence as the only covariate, with effects of male dominance rank on mating success in nonhuman primates (16). Minimal variation was found across subsistence types, yet as a group, humans have significantly lower effects of male status on reproduction compared with nonhuman primates. Point size and line width are proportional to the number of results contributing to each weighted effect size.” From von Rueden & Jaeggi (2016). Men’s status and reproductive success in 33 nonindustrial societies: Effects of subsistence, marriage system, and reproductive strategy. PNAS

Similarly, Dunsworth’s de-emphasis on male competition more generally makes certain common cross-cultural patterns difficult to understand, particularly in light of men’s overrepresentation in committing lethal violence and participating in warfare. As I discussed in my review for Human Nature of Nam C. Kim and Marc Kissel’s book Emergent Warfare in our Evolutionary Past,

Sex differences in participation in warfare are widely documented (Goldstein 2001) and are clearly illustrated by male-biased casualty rates (Beckerman and Lizarralde 1995), capture of women (Otterbein 2000; Walker and Bailey 2013), greater reproductive success for participants (Chagnon 1988; Glowacki and Wrangham 2015), and other material and cultural rewards oriented particularly to male participants (Glowacki and Wrangham 2013; Glowacki et al. 2018).

Later on, Kim and Kissel state, “As we will discuss, the notion that men are more violent than women is a commonly held belief. However, this is not necessarily true” (2018:127). Yet, as far as I can tell, they never revisit this idea again. Although some research has indicated little evidence of sex differences in lower-cost physical aggression (Archer 2000), in every known society males commit significantly more lethal violence than females do, as seen across hunter-gatherer societies (Fry and Söderberg 2013) and nation-states alike, with males committing more than 95% of homicides globally (UN Office of Drugs and Crime 2013). Kim and Kissel fail to address a core ethnographic fact: warfare is a highly gendered behavior, almost exclusively male, and biological sex differences are a key factor in understanding the emergence of warfare.

To conclude, I appreciate Dunsworth’s focus on developmental factors and her reference to hominid ancestry in trying to understand patterns of sexual dimorphism in humans. However, her argument that male competition has been overemphasized across hominids more generally seems misplaced in light of the data provided by Plavcan, and even if recent sexual selection has not been a strong force in contributing to sex differences in height among humans, competition between males has very clearly been an important facet of human societies throughout our history.