Ethnographic Evidence Conflicts With The 'Cold Winters' Hypothesis

There is a popular hypothesis among many self-identified hereditarians which claims that ‘cold winters’ selected for greater intelligence in some human populations. Here is the case laid out by psychologist Richard Lynn in his 2006 book arguing in favor of the framework:

The selection pressure for enhanced intelligence acting on the peoples who migrated from tropical and sub-tropical equatorial Africa into North Africa, Asia, Europe, and America was the problem of survival during the winter and spring in temperate and cold climates. This was a new and more cognitively demanding environment because of the need to hunt large animals for food and to keep warm, which required the building of shelters and making fires and clothing. In addition, Miller (2005) has proposed that in temperate and cold climates females became dependent on males for provisioning them with food because they were unable to hunt, whereas in the tropics women were able to gather plant foods for themselves. For this women would have required higher intelligence to select as mates the men who would provision them. For all these reasons temperate and cold climates would have exerted selection pressure for higher intelligence. The colder the winters the stronger this selection pressure would have been and the higher the intelligence that evolved. This explains the broad association between latitude or, more precisely, the coldness of winter temperatures and the intelligence of the races.

Lynn also expands on this argument in his 2013 paper echoing psychologist J.P. Rushton’s earlier claims on the topic:

Rushton proposes that these colder environments were more cognitively demanding and these selected for larger brains and greater intelligence. There is widespread consensus on this thesis, e.g. Kanazawa, 2008, Lynn, 1991, Lynn, 2006, Templer and Arikawa, 2006. Rushton extends the theory of these climatic selection effects further by proposing that colder environments selected for populations that had greater complexity of social organisation achieved by stronger co-operation between males and a reduction of inter-male sexual competitiveness and aggression (Rushton, 2000, p. 231). The reason for these adaptations was that in the colder climates men had to co-operate in group hunting to secure food and effective hunting required a greater degree of co-operation and a reduction of inter-male sexual competitiveness and aggression than was required in equatorial latitudes, where plant and insect foods are available throughout the year, there is little need for co-operative group hunting is unnecessary, and a high level of inter-male aggression is adaptive for reproductive success.

Unfortunately, these arguments convey a great deal of confusion about how humans interact with their environment, they make erroneous claims about the distribution of cultural complexity across societies, and they demonstrate ignorance of behavioral ecological and cultural evolutionary models that offer more utility in explaining differences in outcomes between societies. A clear illustration of this is Lynn’s discussion of ‘Bushmen’ IQ in his 2006 book:

There have been only three studies of the intelligence of the Bushmen. In the 1930s a sample of 25 of them were intelligence tested by Porteus (1937) with his maze test, which involves tracing the correct route with pencil through a series of mazes of increasing difficulty. The test has norms for European children for each age, in relation to which the Bushmen obtained a mental age of seven and a half years, representing an IQ of approximately 48. In the second study, Porteus gave the Leiter International Performance Scale to 197 adult Bushmen and concluded that their mental age was approximately 10 years, giving them an IQ of 62. In the third study, Reuning (1972), a South African psychologist, tested 108 Bushmen and 159 Africans with a pattern completion test involving the selection of an item to complete a pattern. In the light of his experience of the test, Reuning concluded that it "can be used as a reliable instrument for the assessment of intelligence at the lower levels of cognitive development and among preliterate peoples" (1968, p. 469). On this test the Bushmen scored approximately 15 IQ points below the Africans, and since it is known that Africans have a mean IQ of approximately 67 (see Chapter 4), this would give the Bushmen an IQ of approximately 52.

Lynn, recognizing that some readers may find these numbers absurd, argues for their plausibility. Here is the case he makes:

The three studies of Bushmen by Porteus and Reuning give IQs of 48, 62, and 52 and can be averaged to give an IQ of 54. It may be questioned whether a people with an average IQ of 54 could survive as hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari desert, and therefore whether this can be a valid estimate of their intelligence. An IQ of 54 is at the low end of the range of mild mental retardation in economically developed nations. This is less of a problem than might be thought. The great majority of the mildly mentally retarded in economically developed societies do not reside in hospitals or institutions but live normal lives in the community. Many of them have children and work either in the home or doing cognitively undemanding-jobs. An IQ of 54 represents the mental age of the average European 8-year-old child, and the average European 8-year-old can read, write, and do arithmetic and would have no difficulty in learning and performing the activities of gathering foods and hunting carried out by the San Bushmen. An average European 8-year-old can easily be taught to pick berries, put them in a container and carry them home, collect ostrich eggs and use the shells for storing water, and learn to use a bow and arrow and hit a target at some distance. Before the introduction of universal education for children throughout North America and Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, the great majority of 8-year-old children worked productively on farms and sometimes as chimney sweeps and in factories and mines. Today, many children of this age in Africa, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, through out much of Latin America, and in other economically developing count tries work on farms and some of them do semi-skilled work such as carpet weaving and operating sewing machines. There is a range of intelligence among the Bushmen and most of them will have IQs in the range of 35 to 75. An IQ of 35 represents approximately the mental age of the average European five-and-a-half-year-old and an IQ of 75 represents approximately the mental age of the average European eleven-and-a-half-year-old. The average five-and-a-half-year-old European child is verbally fluent and is capable of doing unskilled jobs and the same should be true for even the least intelligent Bushmen.

Furthermore, apes with mental abilities about the same as those of human 4-year-olds survive quite well as gatherers and occasional hunters and so also did early hominids with IQs of around 40 and brain sizes much smaller than those of modern Bushmen. For these reasons there is nothing puzzling about contemporary Bushmen with average IQs of about 54 and a range of IQs mainly between 35 and 75 being able to survive as hunter-gatherers and doing the unskilled and semi-skilled farm work that a number of them took up in the closing decades of the twentieth century.

Please consider for a moment the abject stupidity of that argument. Richard Lynn is arguing it is plausible that hunter-gatherers surviving in the Kalahari desert are of the same intelligence as 8-year-old European children because children “can easily be taught to pick berries, put them in a container and carry them home, collect ostrich eggs and use the shells for storing water, and learn to use a bow and arrow and hit a target at some distance.” Whether or not those same European children can extract and process complex poisons from insects for use in hunting, anticipate the movement of herds, track game for hours using the limited clues left by a wounded animal, memorize the distribution of water sources, recognize poisonous or nutritious plants, and so on is of course not addressed by Lynn.

However, it is even worse than that—it actually gets below freezing at night during winter in the Kalahari! So, when people like Lynn take the *mean* winter temperature as a metric of ‘cold winters’, like he does in his book, they aren’t actually capturing its harshness. Anthropologist Nancy Howell writes of the Dobe !Kung that,

Following the rainy season of mid-December to April, there are several [Page 8] months of notably cooler weather. By June and July, temperatures reach the freezing point at night on a few occasions and the rhythm of !Kung life is modified to allow people to sit up around the fires at night and sleep in the sun during the day. The cold dry season is followed by the most difficult time of year, when daytime temperatures rise steadily, frequently reaching 43° C (110° F) in September to November. Vegetation is dry and brown, the temporary water sources have dried up, and the people are concentrated around the permanent water supplies, at nine points along the Xangwa and /Xai/xai valleys, living on short food supplies and often with equally short tempers. Late in November, the vegetation starts turning green again, usually some weeks in advance of the welcome first rains of the new year.

Somehow folks like Rushton and Lynn and Kanazawa have convinced themselves that people living in one of the most difficult to navigate and inhospitable parts of the planet have actually got it pretty easy. Kanazawa claims that, “In the tropic and subtropic climate of Africa, plant food is abundant, and food procurement is therefore not difficult at all.” Beyond the absurdity of assuming that all people in Africa subsist on the exact same, apparently equally abundant, plant foods, with no reference to the substantial subsistence or ecological diversity, this is mistaken among the !Kung hunter-gatherers themselves. Richard Lee writes that,

This cold dry season extends from May through August. It is heralded by a sharp drop in nightly temperatures and during 1964 the Dobe area experienced six weeks of freezing or near-freezing nights in June and July. The days are clear and, by tropical standards, cool, often characterized by strong dessicating winds from the south and west with gusts estimated at up to 40 knots. Water is available only at the permanent wells and plant foods become increasingly scarce as the season progresses.

The claim that there is no incentive for long-term planning among tropic and subtropic African populations is contradicted by even the limited evidence we have from other extant hunter-gatherer societies in the region. For example, among the Okiek hunter-gatherers of Kenya, anthropologist Roderic Blackburn writes that,

A man will go to a forest after it has been in flower and the bees are filling the hives. He will spend several days or weeks collecting honey, repairing his old hives and making new ones. If he is ambitious he may go to a forest before the rains so as to repair his hives and make additional ones beforehand so that he will collect more honey than would otherwise be the case. The more ambitious men own as many as 200 hives, the less ambitious perhaps 50. If the rains are good, and one has enough hives, and the honey badger has not damaged many, then a man considers himself pleased if he collects 135 kilograms of honey and honeycombs in a year.

Let’s go back to the claims about hunting and plant foods. Contra the simplistic relationship proposed by Lynn and co., Loren Cordain and his colleagues find that among hunter-gatherer societies in the Ethnographic Atlas,

When the subsistence dependencies of hunter-gatherers were analyzed by latitude (Figure 2, A–D), it was shown that subsistence supplied by hunted animal foods was relatively constant (26–35% subsistence), regardless of latitude (Figure 2B). Not surprisingly, plant food markedly decreases with increasing latitude, primarily at a threshold value of >40° N or S (Figure 2A). Because hunted land animal-food subsistence generally does not increase with increasing latitude (Figure 2B), then the reduction in plant-food subsistence is replaced by increased subsistence on fished animal foods (Figure 2C). As indicated in Figure 2D, the subsistence dependence on combined hunted and fished animal foods is constant in hunter-gatherer societies living at low-to-moderate latitudes (0–40° N or S) and the median value falls within the 46–55% subsistence class interval. For societies living at >40° N or S, there is an increasing latitudinal dependence on animal foods (Figure 2D), which is primarily met by more fished animal foods (Figure 2C). Significant relations exist between latitude and subsistence dependence on gathered plant foods (ρ = −0.77, P < 0.001) and fished animal foods (ρ = 0.58, P < 0.001), whereas no significant relation exists between latitude and subsistence dependence on hunted animal foods (ρ = 0.08, P = 0.23).

So, the claim Lynn and co. make that the colder environments in northern latitudes required more cooperative hunting is not supported in the ethnographic data, instead the decline in reliance on plant foods tends to be made up through fished animal foods. Even more importantly, however, when subsistence patterns are broken down by biome you can see broad categories like ‘cold’ or ‘hot’, or simple metrics like latitude, are less useful than more fine-grained attention to local ecological zones.

From Cordain et al. (2000).

Wicherts et al. (2010) make a related point in their paper noting some of the numerous problems with the ‘cold winters’ hypothesis, writing that,

it is not obvious that locations farther removed from the African Savannah are geographically and ecologically more dissimilar than locations closer to the African Savannah. For instance, the rainforests of central Africa or the mountain ranges of Morocco are relatively close to the Savannah, but arguably are more dissimilar to it than the great plains of North America or the steppes of Mongolia. In addition, some parts of the world were quite similar to the African savannas during the relevant period of evolution (e.g., Ray & Adams, 2001). Clearly, there is no strict correspondence between evolutionary novelty and geographic distance. This leaves the use of distances in need of theoretical justification. It is also noteworthy that given the time span of evolutionary theories, it is hardly useful to speak of environmental effects as if these were fixed at a certain geographical location.

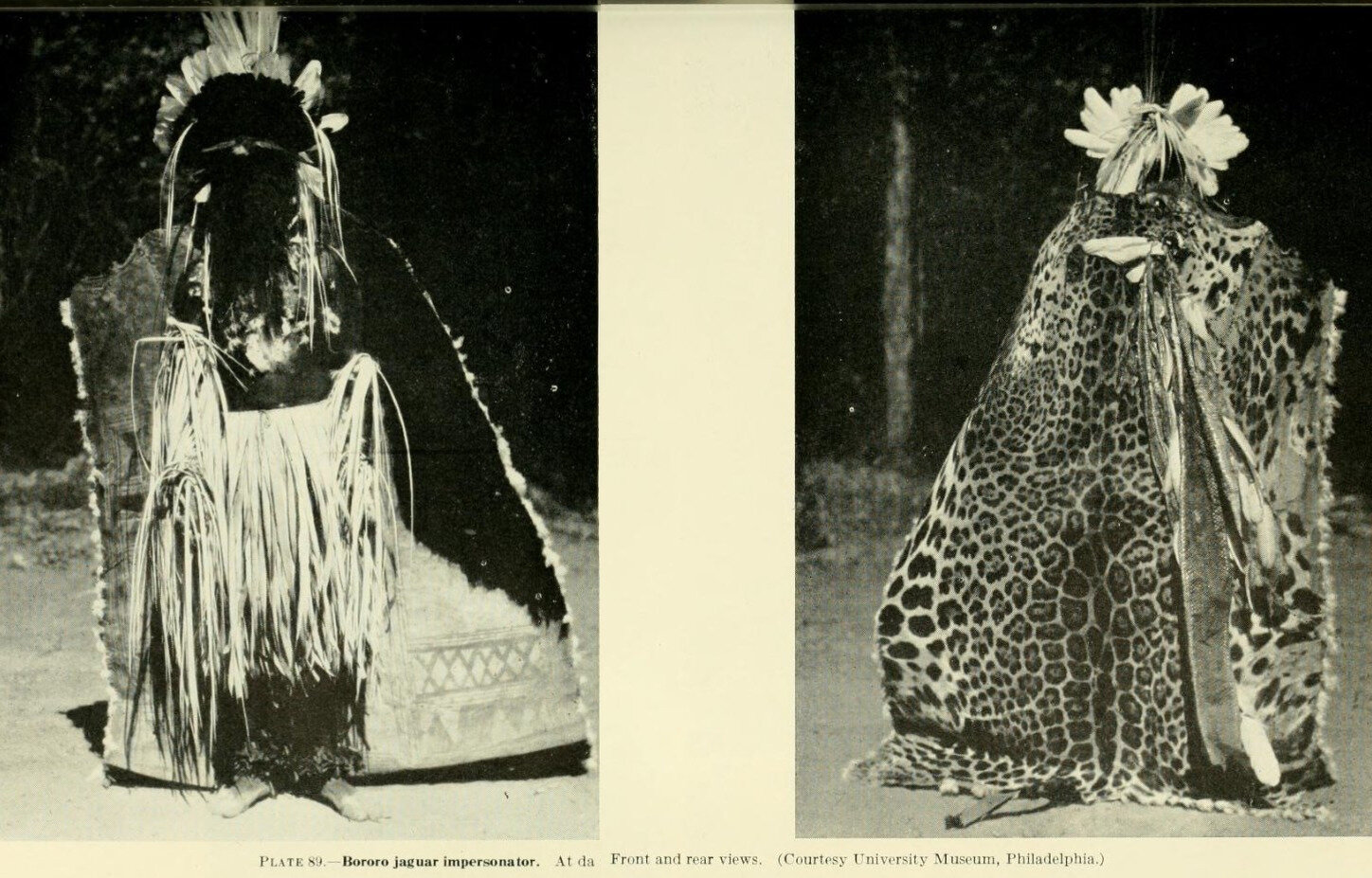

Another component of the cold winters hypothesis is the notion that expansion into northern latitudes required more extensive, complex clothing. This is not necessarily incorrect, but the emphasis made on this point is likely misleading. Consider the Bororo hunter-gatherers of Mato Grasso, Brazil. Their everyday clothing was generally limited to genital coverings, yet more extensive and complex coverings were worn during ceremonies. Anthropologist Vincent Petrullo describes the robe worn during the ‘jaguar dance’:

The dancer was painted red with urucum and down pasted on his breast. His face was also smeared with urucum. Around his arms were fastened armlets made from strips of burity palm leaf, and his face was covered with a mask made of woman's hair. The foreskin of the penis was tied with a narrow strip of burity palm leaf, for these men under their tattered European clothing still carry this string. A skirt of palm leaf strips was worn, and a jaguar robe was thrown over his shoulders. The skins of practically every speeies of snake to be found in the pantanal hung from his head down his back over the jaguar robe, which was worn with the fur on the ontside. The inner surface of the hide was painted with geometrie patterns, in red and black, but no one could explain the symbolism. A magnificent headdress consisting of many pieces, and containing feathers of many birds of the pantanal completed the costume with the addition of deerhoof rattles worn on the right ankle.

Among the Bororo and other warm weather societies, their local climate disincentivized them from habitually wearing more extensive clothing, yet there is little evidence to suggest they were incapable of doing so and plenty of examples to the contrary (Buckner, 2021).

From Lowie (1963)

Rushton and Lynn also make claims about “a reduction of inter-male sexual competitiveness and aggression” among cold weather populations reliant on male hunting, yet in fact the extreme reliance on male subsistence production can exacerbate male-male competition. Among the Copper Inuit, anthropologist Diamond Jenness writes that,

Very few men have more than one wife each. Polygamy increases their responsibilities and the labour required of them; moreover it subjects them to a great deal of jealousy and ill-feeling, especially on the part of men who cannot find wives for themselves. The Eskimo polygamist, therefore, must be a man of great energy and skill in hunting, bold and unscrupulous, always ready to assert himself and to uphold his position by an appeal to force.

Jenness describes one example of wife abduction:

Norak, being unable to obtain a wife elsewhere, laid hands on Anengnak’s second wife one day and began to drag her away. Anengnak caught hold of her on the other side, and a tug of war ensued, but finally Norak, though the smaller of the two, succeeded in dragging her away to his hut and made her his wife.

Further, as I noted in a previous piece discussing the socioecology of polyandry,

Among various Inuit societies, “Exceptionally great hunters are able to support more than one wife; good hunters can support one wife; and mediocre hunters, or those unwilling or unable to take a wife from another man, share a wife.” As we can see, polygyny and polyandry can co-occur, and where some competent, high-status males are able to support multiple wives, lower-status males may end up having to share, or risk having no wife at all.

Also note that this reliance on male hunting can also lead to female-biased infanticide, as I mentioned in a previous article:

Among the Hiwi of Venezuela, and the Ache of Paraguay, female infants and children are disproportionately victims of infanticide, neglect, and child homicide. It is in fact quite common in hunter-gatherer societies that are at war, or heavily reliant on male hunting for subsistence, for female infants to be habitually neglected or killed. In 1931, Knud Rasmussen recorded that, among the Netsilik Inuit, who were almost wholly reliant on male hunting and fishing, out of 96 births from parents he interviewed, 38 girls were killed (nearly 40 percent).

Consider the similarities of the Ache hunter-gathers of the Amazon, and the Inuit of the Arctic—male biased subsistence production, female-biased infanticide, polyandrous unions—the ‘cold winters’ hypothesis cannot explain this but it’s precisely what you’d predict from a behavioral ecology framework. See my discussion of the Asmat hunter-gatherers of New Guinea and their complex social organization in relation to other societies occupying similar ecological zones in different parts of the world.

Bis-pole of the Asmat sedentary fisher-foragers of New Guinea. From Knauft (1993)

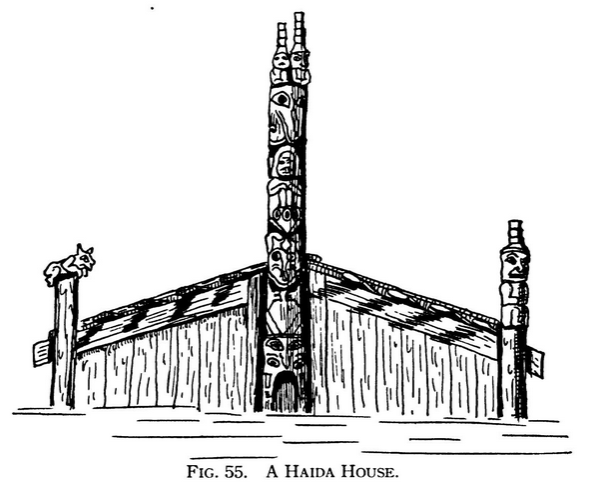

House and totem pole of the Haida sedentary fisher-foragers of British Columbia. From Murdock (1934).

In my view, the cold winters hypothesis has little to offer in its current state, and ultimately is driven by mistaken assumptions about human socioecology.

For further reading see Wicherts et al. (2010).