On secret cults and male dominance

“They told us that Abvwoi was a secret cult, and that if we told women we should be killed and dragged away into the forest. They really did kill people – not in our own time, but two people were killed before us.” - Daniel Bako of Agban village, Kagoro [Nigeria].[1]

“I don’t want to see the sacred flutes. The men would rape me. I would die." —Itsanakwalu, a young Mehinaku woman in her early twenties.[2]

Every contemporary society owes its development to the human predilection for cumulative cultural evolution. From the smallest hunter-gatherer bands with the simplest tools, to the largest, most technologically advanced nation states, everywhere people utilize knowledge passed down through generations and shared among each other that no single individual could ever have accumulated alone. With the benefits of open exchanges of information well-attested, the prevalence across cultures of ritual secrecy, and the monopolization of information, require greater attention.

One of the more surprising elements of secret societies in the ethnographic record is how visible they are. They can be found everywhere, and are particularly well documented across Melanesia,[3] the Amazon,[4] and West Africa.[5] Undoubtedly, there are mixed-sex,[6] and all female,[7] secret societies, but when examining aggressive and domineering coalitions engaged in physical coercion, ritualized deception, and violent punishment of outsiders and taboo violators, these are often comprised entirely of males.[8],[9] These all-male secret societies are best described as ‘men’s cults’, and they can be found among hunter-gatherer societies, horticulturalists, and agriculturalists alike. Many of these secret societies may no longer exist, however I will describe them as they are generally portrayed in the ethnographic material.[10]

The men’s cult represents a conspiracy in plain sight. The ‘men’s house’ is often the largest structure in a village, and built in a position of prestige, at the center or top of a settlement. This is where most adult males and teenage initiates spend the majority of their time when not engaged in subsistence activities. The house can function as a ritual center for the men, and it holds the sacred paraphernalia of the men’s cult, which often consists of masks and/or musical instruments. These objects are usually meant to be kept hidden from women and children. A woman who would glance at the sacred flutes among the Mundurucu of the Amazon would be punished through gang-rape by the males.[11] Across New Guinea, the punishment for a woman who saw the sacred objects was often execution.[12]

Nggwal Bunafunei spirit house (men’s house). From ‘The Cassowary’s Revenge’ (1997) by Donald Tuzin.

Male cult members whirl their bullroarers and play their sacred flutes in private, hidden away from the uninitiated. The women and children are told that these sounds are the voices of their ancestors, and spirit beings. Among the Ilahita Arapesh of New Guinea, men would wear full body costumes during cult ceremonials, while the women would be told they are materialized spirits.[13] Men from neighboring villages were often asked to wear the costumes – and were given yams and sprouted coconuts in return – in order to prevent the women from suspecting it was males from their own community in the costumes.

Arapesh men’s ritual costume. From The Voice of the Tambaran: Truth and Illusion in Ilahita Arapesh (1980) by Donald Tuzin.

While sacred flutes were particularly common among men’s cults in northwest Amazonia and throughout Melanesia, other types of ritual paraphernalia were also widespread. The use of masks and costumes in rituals have been common in secret societies across West Africa. In A History of African Societies to 1870 historian Elizabeth Isichei writes, “masking cults acted...as an agency of social control over women, children, slaves and foreigners…”[14] Ekpe societies in Nigeria had special masks of various colors. Anthropologist H.P. Fitzgerald Marriott notes that, “Women, on pain of death, are not allowed to see the black masks.”[15] Secret societies found across Nigeria had many similarities to those in Melanesia and Amazonia, including a large men’s house used for rituals, the use of bullroarers to indicate the voices of spirits, and male cult members wearing full body costumes to portray spirit beings.

Men’s houses, as well as religious rituals and sacred paraphernalia that are kept secret from women and children, also existed among native hunter-fisher-gatherer societies across Alaska, and hunter-gatherers in Australia. Ethnologist Edward William Nelson wrote that in villages across the Alaskan mainland and the islands of the Bering Strait, the ‘kashim’ (men’s house) was “the center of social and religious life”.[16] While women and children were frequently invited to the kashim for public ceremonies and festivals, “at certain times, and during the performance of certain rites, the women are rigidly excluded, and the men sleep there at all times when their observances required them to keep apart from their wives.” In describing secret societies across Alaska, anthropologist Ben Fitzhugh writes:

“These societies maintained secret knowledge, songs, and dances that gave them the power to emulate evil spirits, devils, and demons in rituals. It is widely reported that the performances of these secret societies were designed to invoke fear in women and children.”

Drawings of Alaskan ceremonial masks. From 'The Eskimo about Bering Strait' (1900) by Edward Nelson.

In the Australian men’s houses, boy initiates would carve sacred boards that were off-limits to women and children, following the traditions of their fathers and grandfathers.[18] In the volume Politics and history in band societies, Annette Hamilton describes land rights in the Australian western desert, writing that, “rights over sacred sites are owned by certain specified men; access to them is forbidden to all women, uninitiated men, and children…”[19] Social institutions are consistently conceptualized in terms that might be best described as ‘religious’, and complex initiation rites are often required for young males to signal the necessary commitment to be integrated into the men’s cult.

Young boys may view their initiation into the cult with a mixture of excitement and dread. Integration into the cult requires undertaking a variety of dysphoric rituals. All Aboriginal societies in the western desert of Australia practiced subincision as a requirement for novice males to progress into adulthood. The underside of the young boy’s penis would be slit, exposing the urethra, which does not heal closed. The practices of subincision act as “badges of full manhood and proof of their right to participate in the sacred life.” Other common initiation practices among male cults include ritual seclusion, piercings, beatings, and inducing nose and penile bleeding.

Among some societies, such as the Sambia (a pseudonym) of New Guinea, initiation rites take on an explicitly sexual character. Boys begin living in the men’s house at about seven to ten years of age. On the third day of their initiation, after rites involving beatings, nose bleeds, and stinging nettles, the young boys are introduced to the sacred flutes. The boys are lined up in a row, while a married man walks past them, placing a small bamboo flute up to each of their lips. The boys are then threatened and intimated into sucking the flute.

"An older initiate shows how to suck the flute." - From 'The Sambia: Ritual, Sexuality, and Change in Papua New Guinea' (2006) by Gilbert Herdt.

Anthropologist Gilbert Herdt writes, “The flutes are thus used for teaching about the mechanics of homosexual fellatio...” The boys are told that, in order to grow big, they must suck the penises and have sex with older boys and elder males. An elder tells them, “Suppose you do not drink semen, you will not be able to climb trees to hunt possum; you will not be able to scale the top of the pandanus trees to gather nuts. You must drink semen...it can 'strengthen' your bones.” They are threatened with death if they should reveal the secrets of the cult.

The Sambian men’s cult has some clear parallels to ancient Sparta, where boys were also separated from their mothers at the age of seven, began to live in the men’s house or men’s camp, were subject to dysphoric rites and rituals, and would also have sexual relationships with older males.[20] The comparison to ancient Sparta is instructive, as Sparta was well-known for warfare, which is quite common across societies with men’s cults. There is a strong cross-cultural association of warfare with dysphoric and traumatic male rituals,[21] which are a recurrent component of the men’s cults.

Many societies with men’s cults would also often practice marriage exchanges with enemy groups, which may help explain some of the male hostility towards females in these societies.[22] The men often consider women to be contaminated or polluting, and menstruating women may be segregated into menstrual huts. Herdt writes of the Sambia, “men's secular rhetoric and ritual practices depict women as dangerous and polluting inferiors whom men are to distrust throughout their lives.” Nelson writes of societies in Alaska that, “During menstruation women are considered unclean and hunters must avoid them or become unable to secure game.” This may be an example of social norms tapping into, and repurposing, human’s natural disgust reaction.[23]

The presence of warfare and marriage exchanges with enemy groups offers some plausible functional explanations for the men’s cults. The men can plan their military excursions while in the men’s house, away from the ears of potential enemy sympathizers (their wives and the wives of the other males). The secret rituals and rites may help socialize young boys into becoming effective warriors. Herdt writes of the various functions of the men’s house:

These include military training, supervision and education of boys in the masculine realm, the transmission of cultural knowledge surrounding hunting magic and warrior folklore, the organization of hunting, some separation or recognition of the differences between men and women, the socially sanctioned use of ritual paraphernalia and musical instruments such as flutes and bullroarers, and so forth. These distinctive customs anchor the men’s world in the clubhouse throughout Melanesia.

A third explanation for the men’s cult is that they represent a way for older males to control the sexuality of young males, to reduce reproductive competition, and increase their own paternal certainty. Of the Ilahita Arapesh, Anthropologist Donald Tuzin writes, “…there was a specific taboo, strong and apparently effective, against premarital sexual contact. This injunction was much stronger for males than for females…”[24] The Ache hunter-gatherers of Paraguay don’t have a men’s cult; however, their social organization does exhibit some similarities in this regard. Boys are forbidden from engaging in sexual activity until they’ve undergone initiation rites conducted by older males, such as a lip piercing and mock club-fights.[25] Across many aboriginal Australian societies, young males were delayed from marriage, while elder males were able to have multiple young wives.[26]

While this pattern of recurring warfare, marriage exchanges with enemies, and control of male sexuality helps explain some aspects of the men’s cults across Melanesia, it’s less clear whether this pattern holds in other parts of the world. The Mundurucu in the Amazon have a history of warfare, but not marriage exchanges with enemy groups. Further, in this society the women seem to have their sexuality policed to a much greater degree than the men. The punishment for a promiscuous woman was the same as the punishment for viewing the sacred flutes: gang-rape, and I can find no mention of any comparable punishment for a promiscuous man. The Mehinaku, also in the Amazon, have strong taboos on male sexual activity between the ages of twelve to fifteen, but are relatively lax on sexual behavior otherwise.

The conspiracy of the men’s cult generates a complimentary mystery: how much do the women and children know? Mehinaku and Mundurucu women are clearly aware of the existence of the sacred instruments, and it seems to be the threat of punishment that keeps them away from challenging the men. Among the Ilahita Arapesh, the women seem to have been generally in the dark about many aspects of the men’s cult, until the men voluntarily revealed their secrets and destroyed the cult in 1984 after decades of Christian missionary activity. Historian Henry Pernet argues that women may be well-aware of the true nature of much of the ritual paraphernalia across many societies with men’s cults, and that potential punishment effectively pressures them go along with the charade, even as they profess seemingly genuine credulity to the ethnographers who interview them.[27]

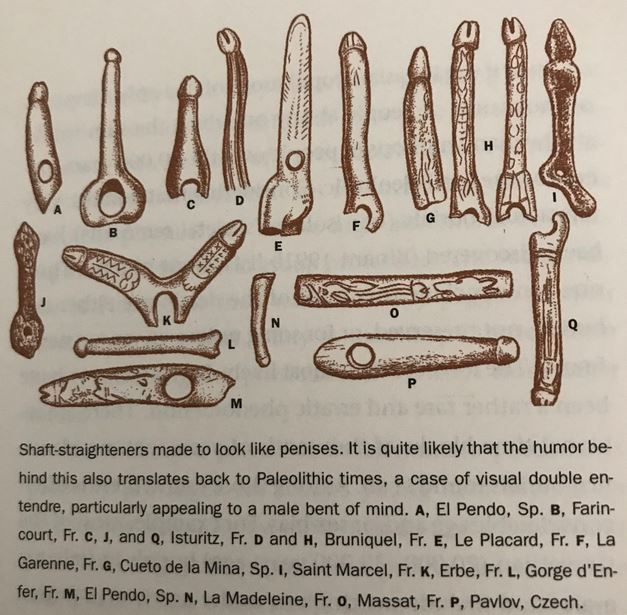

Still, a question remains: why the flutes, and their phallic symbolism? Other than vaguely appealing to psychological universals, a general tendency among males to be fascinated with their own genitalia, and a common human predilection towards symbolism, I don’t have a good answer. Anthropologists who studied men’s cults have often interpreted the symbolism in neo-Freudian and psychoanalytic terms, and while I do not find that approach particularly satisfying, I can’t say that I have a better answer.

The fact that men’s cults can be found across so many diverse small-scale societies may point to similar institutions having existed deep in the past. Archaeologists Oliver Dietrich and Jens Notroff have speculated that the ~12,000 year old site of Göbekli Tepe in modern day Turkey may represent a sanctuary for a men’s cult. Anthropologists D’Ann Owens and Brain Hayden speculate that secret societies (not necessarily men’s cults) may go back to the Upper Paleolithic, and argue that caves during the Upper Paleolithic were used to initiate elite children into secret societies.[28] In R. Dale Guthrie’s book The Nature of Paleolithic Art, he argues that most Upper Paleolithic cave art was made by adolescent boys.[29] Paleolithic art often consisted of hunting scenes, naked women, and phallic imagery, which seems generally consistent with the notion that they were made as part of adolescent boys being initiated into a men’s cult. It is difficult to test these ideas, so they should be interpreted with caution, however they remain a plausible line of speculation.

Drawings of perforated batons found at various Paleolithic sites across Europe. From 'The Nature of Paleolithic Art' (2005) by R. Dale Guthrie.

There is a relatively common tendency among males throughout time and across cultures to seek to monopolize access to resources that can increase their reproductive success.[30],[31],[32],[33] Food, territory, women…knowledge. In my view, the men’s cult represents – in part – a strategy by older males to increase their reproductive success through exercising social control of younger male competitors and women. The fairly common association between men’s cults and warfare, as well as marriage exchanges with hostile enemy groups, also illustrates the important role socioecology plays in the development of these institutions. Considering the common rhetoric about pollution and disease, parasite stress may also be a factor.[34]

Men's cults are not universal, but they are recurrent throughout history and across cultures. Such institutions are antithetical to the kind of free and open society that many in the West prefer today, yet the historical pervasiveness of the men's cult tells us something important about evolution and human behavior.

Future posts will delve more deeply into other cultural traditions and their relationship to human evolutionary history.

[1] Isichei, E. 1988. On Masks and Audible Ghosts: Some Secret Male Cults in Central Nigeria. Journal of Religion in Africa

[2] Gregor, T. 1985. Anxious Pleasures: The Sexual Lives of an Amazonian People. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[3] Herdt, G. 2003. Secrecy and Cultural Reality: Utopian Ideologies of the New Guinea Men's House. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

[4]Murphy, R. F. 1959. Social structure and sex antagonism. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology

[5] Butt-Thompson, F.W. 1929. West African Secret Societies. High Holborn London: H. F. & G. Witherby.

[6] Elmendorf, W.W. 1948. The Cultural Setting of the Twana Secret Society. American Anthropologist

[7] Bosire, O.T. 2012. The Bondo secret society: female circumcision and the Sierra Leonean state PhD Thesis: University of Glasgow

[8] Herdt, G. 1982 Rituals of Manhood: Male Initiation in Papua New Guinea. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[9] Webster, H. 1908. Primitive Secret Societies. New York: The Macmillan Company.

[10] There is certainly significant variation across these societies, however the description that follows here is consistent with the record of numerous men’s cults across Melanesia and the Amazon, in particular.

[11] Murphy, Y. & Murphy, R. 1985. Women of the Forest. New York: Columbia University Press.

[12] Hays, T.E. 1986. Sacred Flutes, Fertility, and Growth in the Papua New Guinea Highlands. Anthropos

[13] Tuzin, D.F. 1980. The Voice of the Tambaran: Truth and Illusion in Ilahita Arapesh Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[14] Isichei, E. 1997. A History of African Societies to 1870. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press

[15] Fitzgerald Marriott, H.P. 1899. The Secret Societies of West Africa. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

[16] Nelson, E.W. 1900. The Eskimo about Bering Strait. Extracts From the Eighteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington: Government Printing Office

[17] Fitzhugh, B. 2003. The Evolution of Complex Hunter-Gatherers. New York: Plenum Publishers

[18] Tonkinson, R. 1978. The Mardudjara Aborigines: Living the dream in Australia’s desert. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston

[19] Hamilton, A. 1982. Descended from father, belonging to country: rights to land in the Australian Western Desert. in Politics and history in band societies. (ed. by Leacock, E. & Lee, R.) New York: Cambridge University Press

[20] Herdt, G. 2006. The Sambia: Ritual, Sexuality, and Change in Papua New Guinea. Belmont: Wadsworth publishing.

[21] Sosis, R. et al. 2007 Scars for war: evaluating alternative signaling explanations for cross-cultural variance in ritual costs. Evolution and Human Behavior

[22] Ember, C. 1978. Men's fear of sex with women: A cross-cultural study. Sex Roles

[23] Curtis, V. et al. 2011. Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behavior. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B

[24] Tuzin, D. 1997. The Cassowary’s Revenge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[25] Hurtado, A.M., & Hill, K., 1996. Ache Life History: The Ecology and Demography of Foraging People. New York. Routledge

[26] Bodley, J.H. 1994, 2017. Cultural Anthropology: Tribes, States, and the Global System. Lenham: Rowman & Littlefield.

[27] Pernet, H. 1992. Ritual Masks: Deceptions and Revelations. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press

[28] Owens, D. & Hayden, B. 1997. Prehistoric Rites of Passage: A Comparative Study of Transegalitarian Hunter – Gatherers. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology

[29] Guthrie, R.D. 2005. The Nature of Paleolithic Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[30] Jaeggi, A.V. et al. 2016. Obstacles and catalysts of cooperation in humans, bonobos, and chimpanzees: behavioural reaction norms can help explain variation in sex roles, inequality, war and peace. Behaviour

[31] Nettle, D. & Pollet, T.V. 2008. Natural Selection on Male Wealth in Humans. The American Naturalist

[32] Betzig, L. 2012. Means, variances, and ranges in reproductive success: comparative evidence. Evolution and Human Behavior

[33] Glowacki, L. et al. 2017. The evolutionary anthropology of war. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization

[34] Fincher, C.L. & Thornhill, R. 2012. The parasite-stress theory may be a general theory of culture and sociality. Behavioral and Brain Sciences