Appeasing the Dead

I’m more…than just…a little curious…

how you’re planning…to go about…

Making your amends…

to the dead. To the dead — A Perfect Circle, The Noose.

Death is an end. It is not quite the end, though. A person dies, yet many of the impressions and feelings they left in the minds of the living continue on.

On one level, the death of a loved one, or a hated adversary, represents the end of a relationship. For the living, however, it is not simply the cessation of an association but a change in its status, with some attendant consequences and obligations that follow.

After an Andaman Islander man has killed a fellow member of his community, there are several precautionary measures considered necessary for him to undertake.

The killer goes to live in the jungle, by himself, for some weeks or months. During this time, he may not handle a bow or arrows. He may not feed himself or touch any food with his hands, though he may be fed by his wife or a friend, who are free to stay or visit with him. His neck and upper lip must stay covered with red paint, and he must wear plumes of shredded wood in his belt and necklace.

After a few weeks, the killer undergoes a kind of purification ceremony. His hands are rubbed with white clay, and then red paint. After this, he washes his hands, and may handle a bow and arrows and feed himself once more.

If any of these precautions are not followed, it is thought, the spirit of the murdered man will have his vengeance.

For the Nuxalk of British Columbia, it is understood that, “The ghost of a murdered person usually tries to avenge himself on his killer,” whose only recourse for protection involves obtaining some small portion of the body or clothing of his victim, such as a tuft of hair or a bit of cloth, or most simply some dirt from above his grave. Once the necessary item is acquired, should the ghost of the victim ever trouble his killer with some kind of sickness, the killer burns the trophy, letting the smoke waft over his body, to destroy the powers of the deceased.

The Onges of the Andaman Islands had a (mistaken) reputation for cannibalism among European outsiders during the 19th century, because while they did not eat those they killed in war, they would cut off their limbs after death and throw them into a great fire, to banish their hostile spirits.

Among the Arunta of Central Australia, after an avenging party has successfully concluded their expedition, they paint themselves with charcoal and wear green twigs on their heads and in their noses, to disguise themselves from the ghosts of those they killed.

This fear of vengeance sought by men who have been killed is a mysterious but not altogether unpredictable sort of negative reciprocity: the conventions and logic of human social interaction can persist even after the death of a participant. Revenge for the death of a loved one is one of the most common motives for killing cross-culturally, so the notion that the ghost of a murdered man would be interested in pursuing his own vengeance is, in some sense, not too surprising.

Stranger though, are the many cases where it not simply enemies but deceased friends and family members who are thought to represent a harmful influence on the living after their death.

Among the G/wi of the Central Kalahari Desert, anthropologist George Silberbauer writes that, “The spirit of the deceased is believed to be malign and resents being deprived of the company of his family and band and will revenge himself on anybody whom he can catch. He will also try to catch somebody from his family or band to keep him company.”

The Kaingang of Brazil consider a widowed person to be inherently dangerous, “for the ghost of the departed clings to its last earthly vestiges in the hair of the surviving spouse…and under the nails…It follows its spouse about wherever it goes, for it is loath to give up its earthly attachments.” Confined in the middle space between the land of the living and the abode of the dead, the ghost is reluctant to give up the relationships and pleasures it enjoyed in life, and trails their surviving spouse wherever they go.

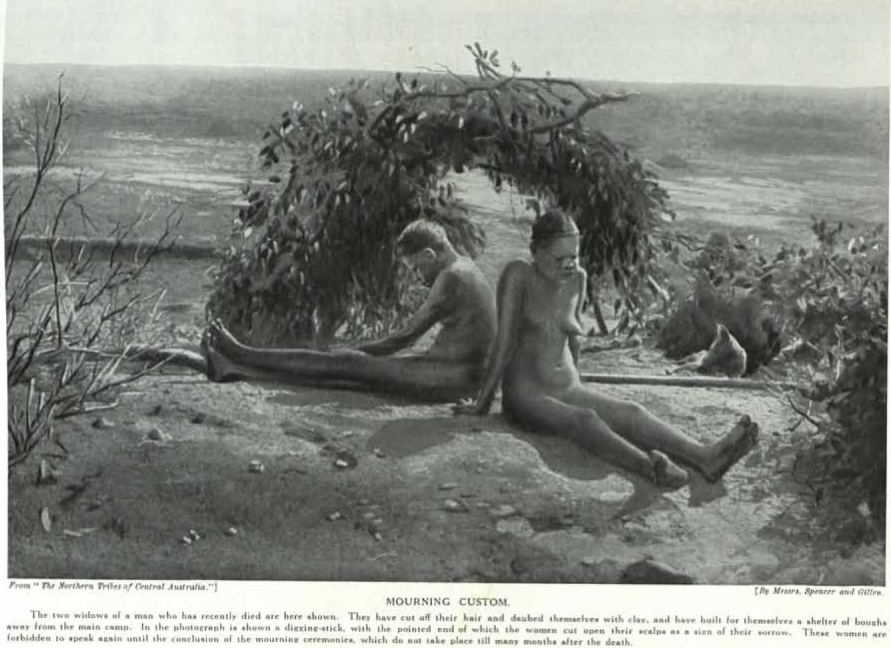

Mourning Custom, Central Australia. "The two widows of a man who has recently died are here shown. They have cut off their hair and daubed themselves with clay, and have built for themselves a shelter of boughs away from the main camp. In the photograph is shown a digging-stick, with the pointed end of which the women cut open their scalps as a sign of their sorrow. These women are forbidden to speak again until the conclusion of the mourning ceremonies, which do not take place till many months after the death." From ‘Customs of the World’ (1922).

The widowed person must live out of camp for some weeks or months, “until the attachment of the ghost is enfeebled.” A widowed husband must obstain from eating the foods he hunted for his wife while she lived, while a widowed wife similarly must not consume foods she cooked for her deceased husband. After this fasting period, the spouse returns to camp with their hair and nails cut, and “is thus freed from the dirt that was so close a link to the ghost.” The return to camp was traditionally an occasion for elaborate ceremony. The spouse’s head would be covered with feathers as a disguise to fool the ghost, while community members engaged in frantic singing and rattling to frighten the ghost away.

Among the Tiwi of Northern Australia, hours are spent on elaborate painted disguises to fool the ghosts, so their graves can be safely approached and proper funerary rites be carried out, to placate their spirits.

From ‘Tiwi Wives’ (1971) by Jane C. Goodale.

Mourning rituals are often explicitly thought to appease the emotions of the deceased. Among the Mescalero Apache of New Mexico,

it is assumed…that the dead are outraged when their possessions are not destroyed, when mourning for them is lax, or when they are referred to disrespectfully. It is also agreed that they tend to linger about the grave (especially for the first four days after death) and strive to return to familiar sights and sounds and companions.

Mike Mountain Horse, a Blood Indian of Canada, described his people’s traditional beliefs about ghosts, and their practices for sending them away, writing that,

If an Indian imagines he hears his name called, he will answer, “Go by yourself.” If is a common belief that a ghost is responsible and should be told to go by himself. But a ghost is not without fear, according to my people. I have been advised by friends on several occasions, while out walking at night time, to take a pliable switch and whip around with it an intervals, at the same time making a loud hooting noise. This is done to scare away any ghosts that may be in close range.

Ghosts, while dangerous in their own right, remain possessed by many of the same concerns and pitfalls faced by the living. They tend to be jealous, lonely figures, resentful of the loss of life’s pleasures, and desperate to return to their friends and family—at least, in the first few weeks or months after death.

Through the following of ritual conventions, the keeping of taboos, and the use of disguise, the dead may be tricked, mollified, and sent on their proper path.