Yanomami Warfare: How Much Did Napoleon Chagnon Get Right?

Since most lethal conflicts among the Yanomamö involve disputes over women at some point in the development of the dispute, the status of unokai [killers] by definition is intimately related to reproductive striving - Napoleon Chagnon, The Yanomamo, 2012.

One of the most acrimonious debates in anthropology over the last few decades revolves around patterns of warfare among the Yanomami forager-horticulturalists of the Amazon. What began as a contentious, but scholarly debate in the late 1980’s/1990’s became a conflict over a variety of incendiary claims made in the book Darkness in El Dorado (2000) by author Patrick Tierney. The book and subsequent media attention ended up derailing what was otherwise a fairly informative discussion addressing the nature of warfare among Yanomami, and how those insights can be applied to other small-scale societies. Rather than relitigating the controversy over Tierney’s book, I want to go back to the scholarly debate between anthropologists Napoleon Chagnon, and his main critic, R. Brian Ferguson.

Chagnon initially gained controversy for his ideas about violence and warfare among the Yanomami – and the potential application of these ideas to small-scale societies more generally – arguing that “homicide, blood revenge, and warfare are manifestations of individual conflicts of interest over material and reproductive resources.” In particular, Chagnon noted that Yanomami men who had killed had greater reproductive success than men who hadn’t. Ferguson contested this claim, arguing that, among other things, this effect is primarily driven by the fact that killers are more likely to be older (older males have more children), and more likely to be a ‘headman’ (headmen usually have more wives and more children).

Regarding his objection about the inclusion of headmen in Chagnon’s sample, this seems like Ferguson is advocating a preferred form of post-treatment bias, by wanting to statistically control for a variable in order to dilute the size of an effect associated with it. 12 of the 13 headmen in Chagnon’s sample were killers (the only non-killer had only recently obtained headman status). If being a killer is, for all practical purposes, a requirement to obtain or keep headman status, then removing headmen from your sample just obscures the way killing can be a pathway to greater power and reproductive success.

Warriors in small-scale societies gaining greater status and marriage opportunities is a fairly common (though not universal) trend. I discussed aspects of this in two articles over at Quillette, and I also noted this pattern in my last blog post discussing head-hunting traditions across cultures, [edit: and see also my more recent commentary over at Behavioral and Brain Sciences with Luke Glowacki].

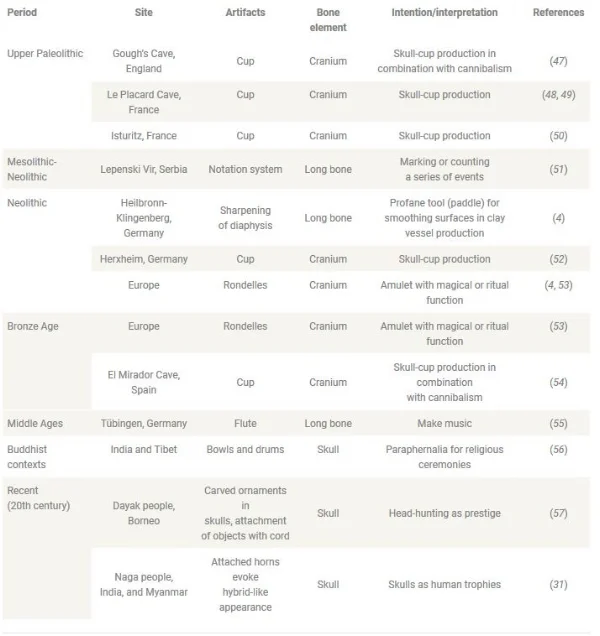

Table from 'The Role of Rewards in Motivating Participation in Simple Warfare' (2013) by Glowacki & Wrangham.

Two other objections Ferguson raised are worth mentioning. Ferguson noted that Chagnon could not account for dead men in his sample (maybe being a killer is associated with greater risk of death, and potentially worse reproductive success overall when including the dead, so only accounting for living men leaves you with a survivorship bias in your sample). This is a reasonable objection, although to my knowledge it hasn’t been adequately tested. It’s also not exactly fatal to Chagnon’s model; it would simply illustrate that being a killer, not unexpectedly, is a risky reproductive strategy, with potentially high-costs but large benefits for success. At larger social scales, you can see this with the examples of Ghengis Khan or Ismael the Bloodthirsty, that being a successful conqueror conferred some pretty substantial fitness benefits.

Although, as those examples show, political jockeying and developing coalitions of other men to be violent on your behalf, potentially reducing your own personal exposure to risky conflict when possible, is quite important, so the success of the headmen among the Yanomami is worth noting.

Further, we’d also expect some stabilizing influence on this type of aggressive behavior, as being indiscriminately violent, or conversely, being unable to defend yourself, are both unlikely to be particularly helpful strategies. Chagnon makes a related point in his reply to Ferguson, noting that, “Being excessively prone to lethal violence may not be an effective route to high reproductive success, but, statistically, men who engage in it with some moderation seem to do better reproductively than men who do not engage in it at all.”

This fits with anthropologist Luke Glowacki and primatologist Richard Wrangham’s work among the Nyangatom pastoralists of East Africa, where men who participated in more low-risk stealth raids had greater reproductive success, while men who participated in more high-risk large battle raids did not have greater reproductive success. Glowacki and Wrangham have also shown that intergroup violence in both chimpanzees and among nomadic hunter-gatherers is often undertaken tactically; aggressors are more likely to attack when they have a numerical advantage and can ambush outsiders who encroach on their territory. Indiscriminate use of violence is not favored, but the tactical use of violence can represent a biologically and/or culturally adaptive strategy. As Chagnon wrote regarding raiding parties among the Yanomami, “The objective of the raid is to kill one or more of the enemy and flee without being discovered.”

Ferguson’s second objection is his argument that the influx of Western goods exacerbated Yanomami violence. This is difficult to test but it would not surprise me if it is true. The Salesian missions in the region distributed thousands of machetes and axes to the Yanomami, and due to unequal distribution and competition for highly valued Western goods such as these, it doesn’t seem unlikely that this may have increased rates of violent conflict.

Much of Ferguson’s work throughout his career has been devoted to reinforcing the point that initial contact with outsiders (particularly Western societies) can exacerbate small-scale warfare, even if ultimately colonial authorities eventually end tribal wars. I cited Ferguson favorably on this point in my Quillette article on colonial contact. This doesn’t mean societies like the Yanomami did not wage war in the past, of course, but it is certainly possible the scale and scope of their war practices were at the high end of its distribution when ethnographers like Chagnon visited them.

On the other hand, Ferguson makes a pretty severe error in attributing essentially all Yanomami conflict to competition over Western goods. While the Yanomami themselves often said their raids were due to revenge or access to women or witchcraft accusations, Ferguson refuses to believe this, attributing everything to basic material factors. I’ll have some posts coming out in the future on traditions of bride capture, revenge raids, and sorcery across cultures, but suffice to say here that these traditions are very common the world over, and generally can’t be attributed to Western influence.

I think Ferguson is missing a pretty big part of the picture here, which Chagnon has highlighted in his own ethnographic work. As Chagnon wrote in his book on the Yanomami, “New wars usually develop when charges of sorcery are leveled against the members of a different group. Once raiding has begun between two villages, however, the raiders all hope to acquire women if the circumstances are such that they can flee without being discovered.”

More controversially, Ferguson also has claimed that Chagnon himself (wittingly or not) exacerbated warfare among the Yanomami. The American Anthropological Association attempted to investigate this question in the aftermath of the publication of Darkness in El Dorado and were unable to come to a determination on this, although they did note an example of Chagnon participating in an attempt at a peace agreement between hostile villages, at great risk to himself.

Tentatively, here are some of my conclusions from this debate:

Successful warriors, among the Yanomami and elsewhere, often do reap social and fitness benefits. Although this is not always going to be true, and excessively, indiscriminately violent males are probably unlikely to do well. Context is important.

The hypothesis that the influx of Western goods contributed to some sort of increase in rates of violent conflict among the Yanomami seems plausible, in my view. How big of an increase I cannot say.

There is no evidence that Chagnon himself exacerbated violent conflict among the Yanomami. Chagnon did give gifts of machetes and pots and other Western goods to the Yanomami groups he studied, so it is, however, possible he may have contributed to the general problem of competition for Western goods. The scale of his gift-giving is dwarfed by the activities of the Salesian missions, however. Ferguson also agrees with this, and argues that the Salesian missions had a much greater impact on Yanomami violence than Chagnon.

I think Chagnon broadly got a lot right. Many of the factors that seem to stimulate violent conflict among the Yanomami revolve around cultural traditions that have been incredibly common the world over, and pre-date Western contact, such as wife capture raids, sorcery accusations and revenge attacks. On the other hand, it seems plausible to me that the influx of highly desired Western goods, and their unequal distribution, due in particular to the activities of the Salesian missions, would add a new contributing source of violent conflict. This contact pre-dated Chagnon’s arrival and continued while he was there. Further, the Yanomami were not small bands of mobile hunter-gatherers; they lived in relatively large villages (sometimes upwards of 400) and practiced horticulture, in addition to hunting and gathering.

While some patterns of Yanomami warfare are informative when considering many other small-scale, and potentially even ancestral, human societies (particularly in relation to wife-capture, sorcery allegations, and revenge raids, which have been documented among quite a few mobile hunter-gatherer groups) the comparison should not be taken too far.