Head in Hands: Notes on the Extraction and Display of Human Heads

Removing the head of a victim, however repellent to Western sensibilities, was not simply an act of gloating triumphalism but was regarded as transferring certain spiritual or supernatural benefits to the head-taker – Ian Armit, Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe, 2012.

Neolithic plastered skulls with shell pieces used as eyes, in situ. From the paper 'The Plastered Skulls and Other PPNB Finds from Yiftahel, Lower Galilee (Israel)' by Milevski et al. (2014), published in Plos One.

Many scholars have remarked on the impressive size and abilities of the human brain, but few have understood the otherworldly allure of the human head. The head is the focal point of social interaction in life – its center of attention is communicated through its eyes, meaning is conveyed by its facial expressions, and language is emitted from its mouth, heard by its ears and interpreted by its brain. In death, it may be no less important; often functioning as an object of veneration or a trophy to be secured by the enemies of its owner.

Evidence for the removal and likely ritual use of human heads goes far back in human history. At the Late Pleistocene (130,000 years ago) Neanderthal site of Krapina in Croatia, the remains of a Neanderthal skull were found with 35 cut marks on the frontal bone. While other fossil material at the site show possible evidence of cannibalism, this skull is unique in that the cut marks are located on a region with very little muscle tissue, and the parallel cuts would not have been useful in removing the scalp, making cannibalism or defleshing unlikely explanations. Anthropologist David Frayer and his colleagues argue that these cut marks represent, “some type of symbolic, perimortem manipulation of the deceased.”

The remains of skulls with cut marks similarly lacking a utilitarian function have been found at the early Neolithic (11,000 – 12,000 years ago) site of Göbekli Tepe in southeast Turkey. Archaeologist Julia Gresky and her colleagues described this find in relation to evidence for the existence of similar ‘skull cults’ that have been found throughout the region, writing that;

In the Pre-Pottery Neolithic [9,000 – 11,600 years ago] of Southeast Anatolia and the Levant, there is an abundance of archaeological evidence for the special status assigned to the human skull: In addition to the deposition of skulls in special places, as attested by the “skull depot” at Tell Qaramel or the “skull building” at Çayönü, human skulls are also known to have been decorated, for example, where the soft tissue and facial features have been remodeled in plaster and/or color was applied to the bone.

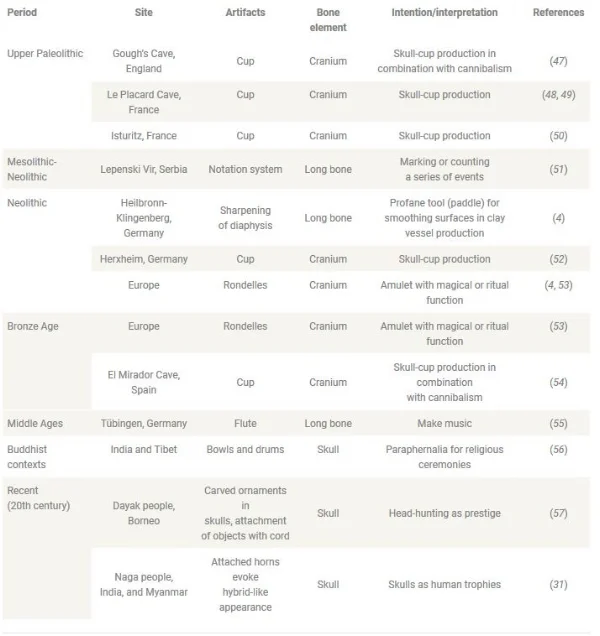

Archaeological finds from all over the world attest to the enduring fascination humans have had with skulls. At Gough’s Cave in England, the remains of skull caps, plausibly used as drinking cups, were found dating back to about 15,000 years ago.

Various archaeological and ethnographic examples of human bone modification. From the paper 'Modified human crania from Göbekli Tepe provide evidence for a new form of Neolithic skull cult' by Gresky et al. (2017), published in Science.

The earliest evidence for decapitation in the Americas goes back to about 9,000 years ago in Brazil, where a skull was found buried with amputated hands carefully laid over the face.

9,000 year old skull with amputated hands placed over the face. From the paper 'The Oldest Case of Decapitation in the New World (Lapa do Santo, East-Central Brazil)' by Strauss et al. (2015), published in Plos One

The practice of extracting the heads of enemies is also well-attested to among a diverse array of societies described in ancient literature. Decapitation is mentioned numerous times in the Bible, such as when David cut off the Philistine Goliath’s head, brought it back to Jerusalem, and showed it to King Saul (1 Samuel 17:54), which is later mirrored by the Philistines cutting off King Saul’s head and publicizing his death among their own people (1 Samuel 31:9). There is also the famous example of Salome’s demand to King Herod that he bring her the head of John the Baptist on a platter (Matthew 14:8).

Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (c. 1607) by Caravaggio

Ancient Assyrian inscriptions contain numerous accounts of kings decapitating the heads of enemies. King Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) boasted, “I gouged out the eyes of many troops. I made one pile of the living [and] one of heads. I hung their heads on trees around the city.” His son, King Shalmaneser III (859–824 BC) claimed, “I mustered (my) chariots and troops. I entered the pass of the land Simesi (and) captured the city Aridu, the fortified city of Ninnu. I erected a tower of heads in front of the city. I burned ten cities in its environs.”

Wall decoration depicting Assyrian warriors carrying severed heads during the siege at Lachish (8th-7th century BC). From the British Museum; photo by Ferrell Jenkins.

The Greco-Roman writer Plutarch described how the Parthians cut off the Roman soldier Publius’s head, attached it to a spear, and displayed it in front of his father, the Roman general Crassus. A Parthian soldier would later cut off Crassus’s own head, which was then brought to the Parthian King Hyrodes, while he was watching the play The Bacchae by Euripides, which itself contains a plot involving a decapitation and the display of a head.

The Greek writer Strabo, in his work Geography, described the practice of headhunting among the Celts, writing that;

In addition to their witlessness, there is also that custom, barbarous and exotic, which attends most of the northern tribes — I mean the fact that when they [the Celts] depart from the battle they hang the heads of their enemies from the necks of their horses, and, when they have brought them home, nail the spectacle to the entrances of their homes.

Celtic headhunting is particularly well-documented among classical sources.

Table noting various classical sources that describe Celtic headhunting. From Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe (2012), by Ian Armit.

While many early archaeological finds point to unknown ritual use of human heads, much of the ancient literature described here involves more practical matters, such as cutting off the head of a hated enemy to offer proof of his death, or publicly displaying decapitated heads to humiliate or terrify rivals. Among more recently documented traditional societies, both the signalling function of headhunting in warfare, as well as the sacred role of the head in ritual life, were described by late nineteenth and early twentieth century ethnographers.

In 1922, anthropologist Ivor Evans described multiple reasons for head-hunting among various societies in Borneo, writing that;

The reasons for head-hunting among Bornean tribes in general seem to have been threefold: firstly, the practice was not without religious significance; secondly, it was considered a sport and the heads regarded as trophies; and thirdly, among some tribes no youth was considered fit to rank as a man until he had obtained a head, the women taunting those who had been unsuccessful as cowards. (Evans, 186)

A similar pattern was identified among societies on the island of Kiwai in New Guinea in 1903 by missionary James Chalmers, who wrote that, “When heads are brought home, the muscle behind the ear is given in sago to lads to eat that they may be strong…The skull is secured, and the more skulls, the greater the honour. No young man could marry, as no woman would have him, without skulls.”

In his volume on Head-hunters (1901), ethnologist Alfred Haddon wrote that, “There can be little doubt that one of the chief incentives to procure heads was to please the women.” In these societies, capturing the heads of enemies is associated with masculine virility, and a young man must seize the skulls of outsiders to be considered a viable partner for a young woman.

The collection and control of heads was considered a source of prestige and power in some societies. In 1896, anthropologist Henry Ling Roth wrote that among the Iban people of Borneo;

…the most valuable ornament in the ruai [veranda] by far is of course the bunch of human heads which hangs over the fireplace like a bunch of fruit; these are the heads obtained on various warpaths by various members of the family, dead and living, and are handed down from father to son as the most precious heir-looms… (Roth, 13)

In The Evolution of War (1929), sociologist Maurice R. Davie further stresses the relationship between headhunting and prestige, adding that, “In Borneo the possession of a large number of heads is also a qualification for the chieftainship, and certain feasts can only be held by a war leader who has been particularly successful against the enemy and has succeeded in taking many heads.” Davie describes a ceremony celebrating a successful headhunter among the Iban people of Borneo, recounting how;

the women, singing a monotonous chant, surround the hero who has killed the enemy and lead him to the house. He is seated in a place of honour, and the head [the trophy he has taken] is put on a brass tray before him, and all crowd around to hear his account of the battle, and how he succeeded in killing one of their foes and bringing home his head. (Davie, 52)

In the recent volume Emergent Warfare In Our Evolutionary Past (2018), anthropologists Nam. C. Kim and Marc Kissel describe a number of traditional headhunting practices, explaining the pattern commonly found across cultures; “For many societies, a warrior’s prestige or spiritual power could be increased depending on the reputation of a defeated adversary, and often the head served as a personal manifestation of that enemy. Such trophies could symbolize a warrior’s prowess and courage.”

Ifugao warrior showing the heads he has taken from his enemies. From The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon (1912) by Cornelis Wilcox.

The reputational effect of being a successful headhunter is often connected to religious notions of warriors capturing the souls of defeated enemies by extracting their heads. Davie notes that, “Another religious motive leading to head-hunting is the belief that the slain become slaves to the victor in the next world. This notion is an incentive to warlike prowess among the Nigerian head-hunters.”

In some cases, these captured souls provide the warrior with protection or spiritual power. For example, among the Jivaro of Peru, anthropologist Michael Harner wrote that, “A man who has killed repeatedly, called kakuram or “powerful one,” is rarely attacked because his enemies feel that the protection provided him by his constantly replaced souls would make any assassination attempt against him fruitless.”

After extraction, heads were often treated to a range of modifications, primarily for long-term preservation or decoration. In the volume Violence and Warfare among Hunter-Gatherers (2016), anthropologist Paul Roscoe described headhunting practices among New Guinea foragers, writing that, “Headhunting raids were sometimes overnight affairs, launched usually on foot, though occasionally by canoe. The heads were brought back to be modeled, painted, and stored as trophies to be used in future "ritual preparation for warfare.””

In 1894, missionary Philip Walsh described a complex treatment process for heads among the Maori, writing that;

All authorities agree in stating that the brain, tongue, eyes, and as much as possible of the flesh were carefully extracted; the various cavities of the skull, nostrils, &c., stuffed with dressed flax; and the skin of the neck drawn together like the mouth of a purse, an aperture being left large enough to admit the hand. The lips were sometimes stitched together, and the eyes were invariably closed, as the Maoris feared they would be bewitched (makutu) if they looked into the empty sockets. This was done by a couple of hairs attached to the upper lids, and tied together under the chin.* The head was then subjected to a steaming process, which was continued until all remains of fat and the natural juices had exuded. Rutherford states that this was done by wrapping it in green leaves, and submitting it to the heat, of the fire. Polack says it was steamed in a native oven similar to that used for food. Those seen by Mr. King were impaled on upright sticks set in open holes in the ground, which were kept supplied with hot stones from a fire close by, while the operator basted them with melted fat.† Each of these processes would equally serve the purpose required. The next stage was a thorough desiccation, effected by alternate exposure to the rays of the sun and the fumes of a wood fire, of which the pyroligneous acid helped to preserve the tissues and protect them from the ravages of insects. A finishing touch was given by anointing the head with oil, and combing back the hair into a knot on the top, which was ornamented with feathers, those of the albatros being usually preferred. The work was then complete.

The extraction and display of heads is not always directly connected to violence or warfare. In Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe (2012), anthropologist Ian Armit writes that, “In a number of ethnographically documented contexts, certain communities retain, display, and venerate the heads of their own kin.” Armit adds that;

These are obtained not through violence but in the course of conventional funerary practices, even if only a small proportion of heads are retained. These may belong to particularly important, influential, or unusual individuals, whose particular life histories made them appropriate foci for communal ritual and memory, but equally they may be chosen quite arbitrarily. Among the Mountain Ok peoples of Inner New Guinea, for example, skulls were displayed in central ‘ancestor houses’ where they were painted, on certain occasions, in the colours of particular clans and played a central role in communal ceremonies. (Armit, 12).

Headhunting is sometimes considered essential to maintaining a thriving, productive society. Armit writes that, “the explanation most commonly offered by practitioners themselves, was that headhunting was necessary to ensure and enhance the fertility of crops, people, and animals.” This connection was made explicit among some societies in Borneo, with the traditional practice of “treating infertile women by placing a trophy head between their thighs.”

In some cases, the heads are viewed as essentially living things, requiring continued sustenance and care. Among the Berawan of Borneo, heads had to be “fed” with offerings, and “kept warm with a fire that never went out.” Anthropologist Peter Metcalf writes that, in 1956, the Berawan lost a number of the skulls they kept in an accidental fire. However, the loss was not lamented, as “Though it was claimed that the heads had the potential to bring benefits to the community, the service of them was considered onerous.”

The recognition that the extraction and display of human heads is not a singular phenomenon, but instead can stem from multiple diverse motivations helps pin down why these practices are quite variable, yet still widespread across cultures. Headhunting can be incorporated into cultural practices of warfare, and used to indicate a society’s strength and power in intergroup conflict. The care and decoration of heads can also be an important part of a society's religious beliefs or practices of ancestor worship.

Human heads, disconnected from their formerly living bodies, have been used variously to terrify enemies, secure status and prestige for an individual and their kin, or honor the dead. Whether religious or secular, the display of human heads has been a relatively common component of human cultural traditions across cultures and throughout history.