Leopard Society and the Man-Leopard Murders

A leopard always dances on the grave of its victim— Okon Bassey, 1945

On February 22nd, 1945, a man named Dan Udoffia was attacked and killed by a leopard in the Ikot Okoro Area of Southeastern Nigeria. At least, that is what the one apparent eyewitness to the attack, Akpan Etuk Udo, would later claim in his statement to police. No one reported the anything suspicious about Udoffia’s death directly to colonial authorities, and it was only after an article appeared in a weekly newspaper over two weeks later (see excerpt below) that an investigation would be prompted.

‘MURDER AT IKOT OKORO – LEOPARD ALLEGED’

‘Leopards, or human leopards as some suspect, have been waging a relentless war on the people of this division, particularly those living in Ikot Okoro Area. Again and again the people have appealed to Government for help. They have wailed for a long time, but no help has been forthcoming. Day after day reports are made of loss of several lives due to the ravages of these ferocious animals. Nobody knows what Government thinks of this state of affairs. Recently the house boy to Court Messenger Okon Bassey was attacked and killed while on his way to tap palm wine near a riverside. The people are like sheep without a shepherd.’

-Nigerian Eastern Mail, 10 March 1945 (Pratten 2007).

The new colonial District Officer to the region, Frederick Kay, apparently read this article and launched a preliminary enquiry into the attack. Udoffia’s body was exhumed, and a post-mortem examination was conducted indicating that Udoffia was killed by two puncture wounds made by a sharp instrument, inflicted by a person, and not from a leopard at all.

With this evidence in hand, Key began conducting interviews and taking statements from witnesses, including the supposed eyewitness to the attack, Akpan Etuk Udo. Anthropologist David Pratten writes that,

In his statement Akpan Etuk Udo said that after tapping palm wine he had been walking home with Dan Udoffia on the evening of 22 February when he heard the sound of a commotion behind him. As he swung round he saw, just seven paces away, a leopard pinning Udoffia to the ground. He shouted and ran at the leopard, which disappeared into the bush. Though Udoffia was wounded he got to his feet and the two men ran home to the court compound in Ikot Okoro. The next day Udoffia’s master and neighbour, Okon Bassey, took charge of the patient and moved him to his own house. Along with Akpan Etuk Udo and Frank Umoren, the court clerk, Okon Bassey marched several miles to fetch Nchericho, a ‘native doctor’, to attend to him, but before dawn on the following morning, 24 February, Dan Udoffia succumbed to his injuries (Pratten 2007).

Case closed it would seem. Except suspicion would soon fall on Udoffia’s employer, Okon Bassy, for his distrustful actions on February 23rd. Pratten adds that, “When Udoffia was moved to Bassey’s house that day several people were known to have visited the victim, including the local headmaster, other schoolteachers and the court clerk,” yet Bassey refused to allow the local doctor to see him, and when Udoffia died Bassey failed to report it to local authorities, and buried him himself.

After ten days’ investigation, Bassey was arrested and charged with manslaughter. Initially, he was not accused of taking part in the attack itself. Local rumors however held that Bassey was in league with two accomplices, who were all part of the same secret man-leopard society.

A week later, Bassey was allowed to return to his station, and the police uncovered a possible motive for what was increasingly looking like a murder. Bassey, his second wife (of five), and Dan Udoffia’s widow were heard by plainclothes police officers quarrelling over Bassey’s insistence on having sex with Udoffia’s widow. Police also took statements from Bassey’s other wives, and while District Officer Kay remained skeptical of any man-leopard society involvement, he was convinced Bassey killed Udoffia to carry on an affair with his wife (there was also apparently a past land dispute involved). Here is how Pratten sums up the results of the case:

Okon Bassey was subsequently charged with murder and the case was heard before a packed Supreme Court, with Mr Justice Manson presiding, on 27 November 1945. Prosecuting for the Crown, Barrister L. N. Mbanefo stated that Bassey had ambushed Udoffia on account of past disputes between them, and disguising himself as a man-leopard seriously wounded his neighbour with a sharp instrument and left him for dead. After the attack Bassey was further accused of refusing Udoffia medical treatment, of concealing him in his house, and of secretly and indecently burying him. Bassey’s defence counsel, Barrister J. M. Coco-Bassey, offered little to refute the charge. His case hinged on calling Bassey’s wives as witnesses to establish his alibi, but their evidence on oath was dismissed under cross-examination as it was contradicted by statements the police had taken from them previously in Ikot Okoro. These statements claimed that Bassey had not been in the compound with his wives at the time of the attack as he had claimed. Bassey’s senior wife, Edima, had stated that Bassey had threatened to kill Udoffia just hours before the murder and that he had taken her to Udoffia’s grave the day after he was buried where he showed her faked leopard pad marks and where he had said that ‘a leopard always dances on the grave of its victim’. With his alibi broken the defence case collapsed and Okon Bassey was convicted on the evidence of his own wives. On 29 November 1945 he was sentenced to death by hanging.

Now, while this may seem like a natural place to conclude a strange and unfortunate tale, this is in fact our starting point, because while Okon Bassey was the first to be convicted of ‘man-leopard’ murder in the Old Calabar region of southeastern Nigeria, he would not be the last, and in total at least 102 people were convicted of man-leopard murder in the region, with 77 of them being executed being hanging, from 1945-1948.

The deep origins of man-leopard assassinations are opaque, however we may find some hints in the history of traditional secret societies in West Africa. The Ngbe (“leopard” in Ejagham) society began spreading in the Cross River Region by 1600 at the latest, with its original functions thought to be rooted in male political alliances and warfare. Ultimately diverse practices and functions grew out of this secret society as it spread across significant parts of Nigeria and Cameroon. Anthropologists Simon Ottenberg and Linda Knudsen write,

These societies helped to centralize trade and political power within each settlement. The members of its senior grade were invariably wealthy traders, politicians, and heads of the community; even some European traders joined (Nair 1972: 18)…In the Efik area and beyond, Ekpe [“leopard” in Efik] was employed to assist in the collection of debts, particularly those involving trade (Northrup 1978: 107), and to frighten, beat, and control slaves. The organization settled disputes, having the authority to fine, and ultimately to decide life or death. The society was important not only in maintaining social stratification but also in keeping peace between communities (Jones 1956:142)

"Southern Etun Ngbe Performance, Nkanda Grade. Middle Cross River.” from Ottenberg & Knudsen (1985).

Yet with British colonial authorities becoming dominant in West Africa in the 19th century, these and other secret societies, while still potent forces, saw a decline in their prominence and power, as traditional warfare was disrupted by colonial police and local political institutions were uprooted by colonial government.

It is important to note that the man-leopard murders are not directly connected to the Ngbe/Ekpe societies referred to above (particularly as they have a wider geographic distribution than those particular societies do). What this does show, however, particularly in the broader historical West African context, is some relevant dynamics in terms of traditional practices of leopard mimicry and ritual violence and secrecy, which may be helpful for understanding what follows.

While much remains mysterious, it is clear that by the late 19th century the problem of ‘man-leopard’ murders was on the radar of British colonial authorities in parts of the region, and concerns about a ‘Human Leopard Society’ in Sierra Leone were growing. Updates in the Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation from 1896-1906 describe ordinances in British Sierra Leone attempting to crack down on the Human Leopard Society, and other related ‘murder societies’ over the years:

‘Legislation of the Empire, 1895’:

No. 15, which bears the somewhat familiar and ordinary title of "An Ordinance to Facilitate the Detection and Punishment of Crime," opens with this weird preamble: "Whereas there exists in the Imperi country a society known by the name of the Human Leopard Society, formed for the purpose of committing murder, and whereas many murders have been committed by men dressed so as to represent leopards, and armed with a three-pronged knife, commonly known as a leopard-knife, or other weapon." Therefore leopard-skins and leopard-knives and a native medicine called "borfima," are duly scheduled, and it is provided that any person wearing or possessing such things, and not being able to show a lawful purpose, shall be guilty of felony, and liable to fourteen years imprisonment. The Ordinance throws no light on the mischievous character of “borfima”.

‘Review of Legislation, 1901’:

Murder Societies. - The law passed in 1896 for the suppression of the "Human Leopard Society" was noticed in our review of the legislation of that year. The preamble of Ordinance No. 29 of 1901 now recites that a Human Leopard Society and an Alligator Society formed for the purpose of committing murders exist principally in the Ronietta district of the Protectorate, and that many murders have been recently committed there. The "plant" used by these societies is described in the schedule thus: (a) leopard skins "shaped or made so as to make a man wearing the same resemble a leopard"; (b) alligator skins shaped or made so as to make a man wearing the same resemble an alligator; (c) a knife with two or more prongs, commonly known as a "leopard knife" or an "alligator knife"; and (d) the native medicine commonly known as "Borfima" or any medicine of a like nature. The law of 1896 made the possession of these articles a criminal offence. Now the powers of search for them are strengthened; and suspicion that these murders are committed with the cognisance of the chiefs is shown in the clauses directed against chiefs. Any chief who encourages or abets the celebration in any village of any "customs" of the proscribed societies, or fails to report the same to the police, is liable to a fine of '500 or imprisonment for a year. A still stronger measure is a power conferred on the Governor in Council to order the arrest and detention of " any such chief or sub-chief as may be deemed expedient for the maintenance of peace and order and the suppression of the Human Leopard Society and Alligator Society." Any such chief may also be deported by the Governor. The Ordinance was to be on trial until the end of 1902.

‘Review of Legislation, 1905’:

Murder Societies. - We noted last year the continuation of the Ordinance for the suppression of the "Human Leopard Society." It is again continued to the end of 1906. In 1904 there were five cases of these murders in one district of the Protectorate, forty-seven persons being tried and twenty-eight convicted of murder.

Kenneth James Beatty wrote a book, Human Leopards: An account of the trials of human leopards before the special comission court; with a note on Sierra Leone, past and present (1915), discussing the colonial authorities’ investigations into the ‘Human Leopard Society’, as well as the society’s continued activities at the time of his writing;

A small girl aged about seven years was killed at Nerekora toward the end of December, 1912; two days later another small girl about twelve years of age was killed at Bafai; and early the following month another girl aged about twelve to thirteen years was killed at Nerekora. All these deaths were at first attributed to attacks by bush leopards, but the evidence given by various witnesses was to the effect that these three girls were murdered by members of the Human Leopard Society.

In 1916 sociologist H. Osman Newland described witnessing what seems to have been an abduction by a Human Alligator Society member in Sierra Leone, writing that,

In a creek far up the Rokelle river I saw in broad daylight a runaway black who was being tracked as a thief seized by what appeared to be an alligator. But instead of being sucked down into the water he was literally "carried" along the reeds into the bush. The boys who were following him up instantly gave up the chase and stopped me, saying the river god had taken him. I had seen enough alligators, however, to know all their movements, and I guessed the truth, though I allowed them to think I believed them, as I had no desire to become a " dangerous " person in a secluded part of the world where Nature rules.

Beatty also described the formation of a Human Baboon Society early in the 20th century in Sierra Leone,

During the month of May, 1913, a small girl was killed near the village of Bokamp, and, according to statements made by persons who turned informers, she was murdered by members of the Human Baboon Society. Their statements were to the following effect: That this Society was formed about six years ago, and consists of twenty-one members made up of eleven men and ten women; that seven victims, all young children, had been provided at various times for the Society; that at their meetings one of the members of the Society dresses himself in a Baboon skin and attacks the victim with his teeth; that the spirit of all members of the Society becomes centred in the person who is for the time being wearing the Baboon skin, which, when not in use, is kept in a small forest, where it is guarded by an evil spirit, and that the “Baboon” bites pieces out of the victim which the other members of the Society devour.

The only explanation that the informers could or would give as to the objects of the Society was that the founder of it had quarrelled with his tribal ruler, who he alleged liberated one of the founders’ slaves and placed him in authority over him; that he, the owner of the slave, became so incensed that he turned himself into a “witch” and induced others to join him in doing “evil things.”

Beatty notes that more ordinances continued to be passed to crack down on the Human Leopard and other animal ‘murder societies’, in 1909 and 1912, with “A dress made of baboon skins commonly used by members of an unlawful society,” among the banned items.

Another relevant source on this topic seems to be the book African Jungle Doctor (1952) by Werner Junge, with information on man-leopard murders in Liberia. I haven’t been able to get a copy yet, and will update this post when I do, but here is how economic historian Fred van der Kraaij describes it,

In 'African Jungle Doctor', a German doctor describes his ten years in Liberia. Dr. Werner Junge went to Liberia in 1930 to establish a mission at Bolahun, in the heart of the jungle, and he spent two years in running the hospital there. He was then transferred to the coast, and carried on the same kind of work at Cape Mount until 1940. Dr Junge was confronted many times with activities of both the Crocodile Society and the Leopard Society. He extensively describes six cases of ritual murders or murder attempts which he had to deal with as a medical doctor. One of his experiences reads as follows:

"There, on a mat in a house, I found the horribly mutilated body of a fifteen-year-old girl. The neck was torn to ribbons by the teeth and claws of the animal, the intestines were torn out, the pelvis shattered, and one thigh was missing. A part of the thigh, gnawed to the bone, and a piece of the shin-bone lay near the body. It seemed at first glance that only a beast of prey could have treated the girl's body in this way, but closer investigation brought certain particularities to light which did not fit in with the picture. I observed, for example, that the skin at the edge of the undamaged part of the chest was torn by strangely regular gashes about an inch long. Also the liver had been removed from the body with a clean cut no beast could make. I was struck, too, by a piece of intestine the ends of which appeared to have been smoothly cut off, and, lastly, there was the fracture of the thigh - a classic example of fracture by bending." (Junge, 1952: p. 176).

So, what of Okon Bassey and the case referred to at the beginning of this post? One possibility is there was a real leopard attack which he opportunistically took advantage of, bringing Udoffia home, allowing him to die and then burying him himself. This scenario would require the forensic examination to be mistaken, and Bassey’s wife to be lying about the leopard print confession (or perhaps Bassey, for some strange reason, decided to commit to such an act and impersonate a man-leopard after the fact). It also would mean Bassey was especially (un)fortunate that a personal rival in Udoffia happened be the target of the leopard attack.

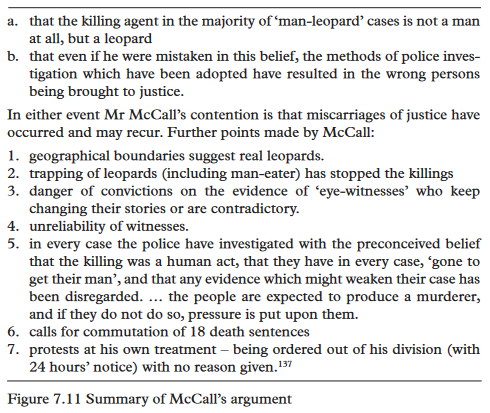

One challenge that arises is that a District Officer, J. A. G. McCall, continued to maintain decades after the fact that probably all of the ‘man-leopard’ murders in Nigeria from 1945-1948 really were done by actual leopards, and not men at all! The figure below sums up his argument. Possibly he is correct about some or maybe many cases but there is a broader regional pattern going on here, with firsthand accounts and observations going back a century or two across multiple countries, that cannot be explained by the particular deficiencies of colonial investigations in one region of Nigeria over the course of a few years.

Summary of former district offer J.A.G. McCall’s argument, from The Man-Leopard Murders: History and Society in Colonial Nigeria (2007) by David Pratten.

At any rate, my speculative view is that Bassey did commit the killing, but that he was not actually a member of any ‘Human Leopard Society’, though he was familiar enough with the method or the stories to attempt to mimic it. It seems he bungled the attempt to a significant degree, failing to kill Udoffia in his initial attack, exposing himself to significant added risk by bringing him back to his home and burying him himself, and then apparently confessing to his wife about fabricating leopard prints. One would think someone better trained or more experienced in the method would likely have had an easier time getting away with it, hence the common pattern (including even in Bassey’s case) of witnesses identifying attackers as leopards. Although, in the Bassey case, it is strange that multiple seemingly respectable people apparently visited Udoffia while he was dying in Bassey’s house (with the exception of the doctor who was refused entry) and don’t seem to have said anything...

I think what happened overall is as the methods of ‘Human Leopard Societies’ were more publicized and spread it led to copycats beyond those who were initiated into more established groups, and the tactics were sometimes used by independent individuals looking to dispose of enemies, or entrepreneurs looking to create their own societies. This is how you get multiple disconnected ‘Human Leopard Societies’ in different West African countries, and the emergence of ‘Human Alligator Societies’, ‘Human Baboon Societies’, etc. On the other side, it also may have led to scapegoating accusations of rivals being members of the widely known and feared ‘The Human Leopard Society’, alleged to have committed killings that may have really been done by actual leopards in some cases.

One commonly reported motive for ‘Human Leopard Society’ killings, at least in Sierra Leone and possibly Liberia, is to extract human body parts to be used in a supernatural ‘medicine’ bag known as Borfima (previously referred to in the colonial ordinances quoted above). William Brandford Griffith, a British colonial administrator in the Gold Coast during the 19th century, describes what the Sierra Leone investigations found in the early 1900’s, writing that, “The trend of the whole evidence showed that the prime object of the Human Leopard Society was to secure human fat wherewith to anoint the Borfima. The witnesses told us how the occasion of a murder is used to "blood" the Borfima, but the potency of this terrible fetish depends upon its being frequently supplied with human fat. Hence these murders.”

Kenneth James Beatty provides a witnesses’ description of being initiated into a Human Leopard Society in Sierra Leone, emphasizing the importance of the Borfima,

One of the witnesses was a boy aged eighteen years. His story was that one evening in the previous year, as he was returning home from a visit to a neighbouring village, night overtook him, and by mistake he took a path leading to the Poro bush at Powolu, where he fell into a number of people. He spoke to them, but no one answered. He then got afraid and commenced to run away, when he was seized by some one who was assisted by several others to make him a fast prisoner. He was then dragged inside the Poro bush and a discussion took place, which he was able to hear, as to whether they should kill him or not. The majority of the members were for immediately killing him in accordance with the rules of the Society, but it was pointed out that another victim had already been secured, and further that as their prisoner was the son of a man of some importance his absence might give rise to some awkward inquiries. It was therefore agreed to give him the alternative of becoming a member of the Society or of being immediately killed. The witness stated that he agreed to join the Society. Borfima was then brought, and the "big man" of the Society explained to him that the Borfima was the "mother" of the Society and should be treated with the greatest veneration ; that they were its children and therefore brothers to each other, and in order to join him to their brotherhood some of his blood had to be given to the Borfima to drink ; that when the blood was taken from him he should bear the pain inflicted bravely and should not utter a sound, as otherwise it would displease their " medicine " and might result in his being punished in some unexpected way. The "Master" then marked him on the left buttock by cutting a slice of flesh away and rubbing the blood that exuded from the wound on to the Borfima. He was then made to swear an oath on the Borfima not to reveal the secrets of the Society, and was forced to be present and witness the killing of a girl who had been brought to the Poro bush, and was made to eat some of the flesh of this victim.

Although there was no direct evidence apart from that of accomplices, it was clear from the testimony of independent witnesses that all these persons were so connected with the Society as to make it desirable to have them removed from the Grallinas District, where it was stated they exercised great influence over the people. All these men, with the exception of eight sub-Chiefs who absconded to Liberia, have since been deported to the Karina and Koinadugu Districts of the Protectorate

I will end with the thoughts of the first district commissioner of Sierra Leone, T.J. Alldridge, who described a ‘Human Leopard Society’ in Sierra Leone in 1901, and his optimism about their decline, thusly,

Before the native rising in 1898, when an abortive attempt was made to put an end to British and all other civilising influences, a part of the Sherbro known as the Imperri country had long been notorious for possessing a medicine peculiar to the place, called Borfimor (a contraction of Boreh fina medicine bag). This Borfimor was a solid preparation, apparently harmless in itself until anointed with human fat, when it became an all-powerful fetish. Of course to obtain human fat people must be killed, and to procure victims the notorious Human Leopard Society was formed. The Imperri was the great centre of this institution. It does not appear to have been of any very great age, possibly not more than forty years or so old. I remember to have been told, some twenty years ago, that it was then merely a family arrangement, the members working only among their own relatives; and that at the committee meetings of the society a relative of some member was selected, told off to be the next victim, and subsequently waylaid and killed by a man in the guise of a leopard, who rushed upon the unsuspecting victim from behind, and planting a three-pronged knife of special make in the neck, separated the vertebra, generally causing instantaneous death. The body was then opened, and some of the internal parts were removed for the purpose of obtaining the fat, which was considered necessary to preserve the magical powers of the Borfimor. The Borfimor was a highly prized fetish, believed to be a panacea against all evil and capable also of procuring all good.

The society after a time becoming too extensive to remain a mere family concern, it appears to have been changed into a public institution ; that is any victim could be taken from the general community, and we know as a fact that the lives of many innocent persons were sacrificed in this manner.

The modus operandi for gaining adherents seemed to be this. When a visitor appeared in any village he was invited to partake of food, in which was mixed a small quantity of human flesh. The guest all unsuspectingly partook of the repast, and was afterwards told that human flesh formed one of the ingredients of the meal, and that it was then necessary that he should join the society, which was invariably done. The initiation fee was the providing of a victim; but it did not necessarily follow that the new member should himself slaughter the victim, he need only furnish him; there were persons who, upon payment, would carry out the murder.

Shortly before the rising it was found that the number of victims to the Leopard Society was rapidly increasing, and, as the greatest secrecy was observed, it was next to impossible to bring the criminals to justice; even the relatives of the victims being too terrified to divulge the smallest thing. For instance, when a witness was examined, the same answer was always given in reply to the question:

"What did you see ?"

“Nothing. I only felt a great wind rush by."

My own opinion was that they never did see anything, because the victim was always in a secluded spot near a thick bush. The leopard never went any distance, he was always in such a position, near an opening in the bush, that he could retreat instantly.

…

Happily the persistent and effective measures adopted by the Government have been so successful that I quite believe the Human Leopard Society is now simply a matter of history.